Gerd Arntz

(1900 – 1988) and Isotype

13 October– 13 November 2010

In the light of growing inequality in western societies as well as on a global scale, Gerd Arntz’s acute observations of interbellum Europe and the consequences of the societal divisions of that time, come as a timely reminder of the dangers such polarisation poses. In spite of obvious disparities of the political climate of then and now, the connection between inequality and the emergence of ideology and demagogy is nevertheless striking.

Gerd Arntz is one of the more unusual, if less well-known, artists of the Weimar Era. Like his more famous contemporaries George Grosz and John Heartfield, Arntz wanted to strip art of bourgeois preciousness. In order to efface all evidence of his individual hand, he invented a stylized vocabulary of symbolic forms. His predilection for the flat, black and white tonalities of woodblock further served to obliterate the artist’s personal touch. Nevertheless, his incisive visual analysis of German society, corruption and political factionalism can hardly be considered impersonal; even in stark black and white, Arntz’s work reveals the artist’s political predilections and idiosyncratic viewpoint.

Arntz was born in the small industrial town of Remscheid, near Solingen, into a family dominated by business and factory owners. Although he played with the workers’ children while he was a boy, Arntz always knew that his family expected him to remember that as a member of the ruling class he should stay out of the workers’ struggle for rights. Prior to the First World War (where he served with the Prussian field artillery for half a year), his contact with art involved little more than fleeting visits to exhibitions and lectures. After the war, Arntz entered one of the family businesses, the Eisenfabrik Greb & Co., as a common factory worker. These experiences would inspire his later woodcuts.

In 1919, Arntz enrolled in the Düsseldorf Art School and quickly became part of a revolutionary circle of young artists who called themselves, Das Junge Rheinland (Young Rheinland). Opposing the conservative instruction at the school, Arntz derived his own knowledge of art from contemporary publications such as Der Sturm, Die Aktion and Die Ziegelbrenner. Arntz was also connected to the Cologne-based ‘progressive artists group’ (‘gruppe progressiver künstler’) which included figures such as Seiwert, Hoerle and August Sander.

In 1920, he joined an initially loose group of Communist artists, who later organized and demonstrated against the military and police. He created woodcuts for the ‘Allgemeine Arbeiter Union’ (General Labor Union) as well as the Communist ‘Intenationale Arbeiter Hilfe’. In 1925, he took over Otto Dix’s studio in Düsseldorf, and this served to intensify his creative concentration and increase his output.

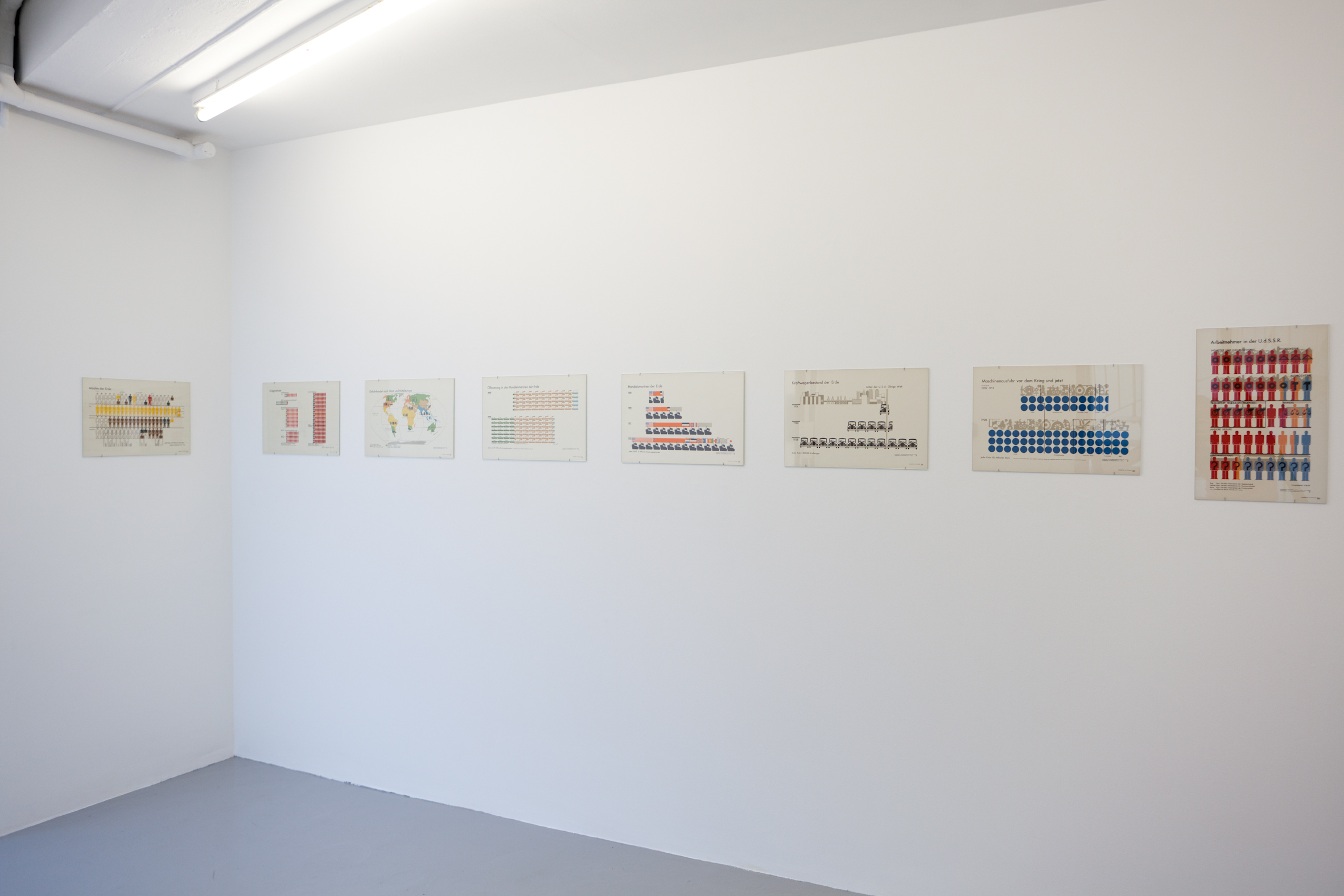

From 1926 Otto Neurath sought his collaboration in designing pictograms for the Vienna Method of Pictorial Statistics (Wiener Methode der Bildstatistik; later renamed Isotype). From the beginning of 1929 Arntz worked at the Gesellschafts- und Wirtschaftsmuseum (Social and Economic Museum) directed by Neurath in Vienna. Eventually, Arntz designed around 4000 pictograms. Between 1931 and 1934 he travelled periodically to the Soviet Union (along with Neurath) in order to help set up the ‘All-Union institute of Pictorial Statistics of Soviet Construction and Economy’ commonly abbreviated to ISOSTAT.

Throughout his career, Arntz’s work consisted of industrial scenes, city views, and numerous depictions of workers rebelling against capitalist owners and the police. The individual figures in his woodcuts represented statistics, and the images were often interspersed with graphs and accompanied by articles expounding upon the status of the working class.

In 1934, Arntz emigrated to The Hague, where he continued to produce woodcuts and linoleum cuts until the end of his life. During an artistic career spanning 50 years, he has continually criticised social inequality, exploitation and war in clear-cut prints- activism through artistic means.